- Home

- Philippe Besson

Lie With Me Page 2

Lie With Me Read online

Page 2

I can imagine everything. And I don’t deprive myself of doing so. On certain days, T.A. is a bohemian child from a family sympathetic to the May ’68 riots. On other days, he’s the wanton son of a bourgeois couple, as the children of uptight parents often are.

It’s my obsession with inventing characters. I told you about this.

In any case, I like to repeat his name to myself in secret. I like to write it on scraps of paper. I am stupidly sentimental: that hasn’t changed much.

So, that morning I stand on the playground and secretly stare at Thomas Andrieu.

It’s a moment that has occurred before. On many occasions, I’ve briefly cast an eye in his direction. It’s also happened that I’ve passed him in the hallway, seen him coming toward me, brushed up against him, felt him receding behind my back without turning around. I’ve found myself in the lunchroom at the same time, him eating lunch with the guys from his class, me with my friends, but we’ve never shared the same table; the classes don’t mix. One time I spotted him as he stood on the dais during a class, making a presentation. Certain classrooms have windows and this time, I slowed down to study him. He was too busy doing his presentation to notice me. Sometimes he sits alone on the steps in front of the school and smokes a cigarette. I caught his blind gaze once as the smoke evaporated from his mouth. At night, I’ve seen him leave the school, headed to the Campus, a bar that adjoins the school along the National 10 highway, probably to meet up with friends. Passing in front of the windows of the bar, I recognized him drinking a beer, playing pinball. I remember the movement of his hips pressing against the pinball machine.

But there has never been a word exchanged between us. No contact, not even inadvertently, and I always stopped myself from lingering so as not to arouse his surprise or discomfort at being stared at.

I’m thinking he doesn’t know me at all. Of course he’s probably seen me, but there can be nothing fixed in his memory, not the slightest image. Maybe he’s heard the rumors about me, but he doesn’t mix with the ones who whistle at and mock me.

There’s no chance either that he’s heard the praise the teachers have given me: we’ve never been in the same class.

To him, I’m a stranger.

I’m in this state of one-way desire.

I feel this desire swarming in my belly and running up my spine. But I have to constantly contain and compress it so that it doesn’t betray me in front of others. Because I’ve already understood that desire is visible.

Momentum too; I feel it. I sense a movement, a trajectory, something that will bring me to him.

This feeling of love, it transports me, it makes me happy. At the same time, it consumes me and makes me miserable, the way all impossible loves are miserable.

I am acutely aware of the impossibility.

Difficulty, you can cope with; you can deploy ruses, try to seduce. There is beauty in the hope of conquest. But impossibility, by nature, carries with it a sense of defeat.

This boy is obviously not for me.

And not even because I’m not attractive or seductive. It’s simply because he’s lost to boys. He’s not for us, for those like me. It’s the girls who will win him.

Not only that, all the girls are in his orbit. They circle him, constantly seeking his attention. Even those who feign indifference do so only to win his favor.

And him; he watches what they do. He knows that they find him attractive. Good-looking guys always know it. It’s a calm kind of certainty.

Sometimes he lets them approach. I’ve already seen him with a select few, usually the pretty ones. Immediately I feel a fleeting stab of jealousy, a sense of impotence.

But that being the case, most of the time, he seems to keep the girls at a distance, choosing the company of his guy friends. His preference for friendship, or at least the camaraderie that comes with it, seems to outweigh any other consideration. And I’m surprised, precisely because he could easily use his beauty as a weapon; he is at the age of conquests, when one often impresses others by multiplying those conquests. However his reticence does nothing to feed a secret hope in me. It just makes him even more appealing because I admire those who don’t use what they have at their disposal.

He also likes his solitude. It’s obvious. He speaks little, smokes alone. He has this attitude, his back up against the wall, looking up toward the sun or down at his sneakers, this manner of not quite being there in the world.

I think I love him for this loneliness, that it’s what pushed me toward him. I love his aloofness, his disengagement with the outside world. Such singularity moves me.

* * *

But let’s come back to that winter morning in 1984. It’s a winter of violent winds, bad weather, shipwrecks in the English Channel and snowstorms on the mountains, we see the rush of these images on the morning news. It’s a morning that should have been like all the others, consumed by my desire and his ignorance of it. Except on that particular morning, the unexpected happens.

As recess draws to a close and the bell rings, announcing the beginning of class, students leave the biting cold of the playground and go back into the hallways, talking mostly about politics, television shows, and our next vacation, coming in February.

Nadine, Genevieve, and Xavier head off to get their school bags from the student lounge, leaving me alone. I’m crouched down trying to find my biology textbook in the mess of my backpack when suddenly I sense a presence beside me. I immediately recognize the white sneakers. It’s excruciating. Slowly, I raise my head to look at the boy above me. Thomas Andrieu is standing there, also alone. He’s framed by a cloudless blue sky, cold sun rays behind him. His friends are probably taking the stairs back up to class. Later he will tell me that he invented a pretext for them to go ahead without him, saying he had to pick up a magazine at the library, or something like that. He stands there in the winter cold with me at his feet. I get up, surprised, trying not to betray my confusion and fear. I think he might punch me. The idea crosses my mind that he could beat my face in without a witness. I don’t know why he would do such a thing; maybe the insults are no longer enough and he has to do something more concrete. In any case, I tell myself it’s in the realm of possibility, that it can happen—which says a lot about the antipathy I believe I provoke, but also my oblivion, because instead he calmly says: I don’t want to go to the lunchroom today. We can eat a sandwich in town. I know a place. He gives me an address and an exact time. I look at him for a moment and then say that I’ll be there. He briefly closes his eyes, as if in relief. And then he’s gone, without saying another word. I remain dumbly rooted to the spot with my biology book in my hand before crouching down again to close my backpack. I know that this scene just happened, I’m not crazy, and at the same time it seems entirely unbelievable. I scan the asphalt tarmac, the emptiness of the playground, surrounded by a growing silence.

* * *

For a long time I will return to this moment, a moment in which a young man approached me with a confident stride. I think of it as the perfect little crack in an extraordinarily brief window of opportunity.

If I had not been abandoned by my friends, if he had failed to convince his to leave him behind, this moment would not have taken place. It could have almost never happened.

I try to figure out the part that chance played, to assess the nature of the risk that led to the encounter, but I don’t succeed. We are in the land of the unthinkable. (Later he will tell me that he waited for the right moment to approach me but until that morning it had never arisen.)

In later years, I will often write about the unthinkable, the element of unpredictability that determines outcomes. And game-changing encounters, the unexpected juxtapositions that can shift the course of a life.

It starts there, in the winter of my seventeenth year.

* * *

At the given hour, I push open the door of the café.

It’s at the end of the town. I’m surprised by the choice of the place, since i

t’s not at all central, or easily accessible. I think: He must like places away from the crowd. I do not yet understand that he obviously chose it to be out of sight. I am in this state of innocence, this stupidity. If I were used to exercising caution, or had developed the art of not responding to questions—but I barely know anything yet of concealment, of the clandestine.

I discover it there in this nearly empty café, just at the edge of town. The people here are only passing through. They’re people on road trips taking a break before resuming their journeys, or gamblers who bet on the horses stopping by just to redeem a winning ticket. Or the glassy-eyed old boozers leaning on the counter, railing against the socialist-communist government. People who don’t know us, in any case, for whom we represent nothing and to whom we will say nothing. People who will forget us the moment we leave.

He’s already there when I cross the threshold. He arranged to arrive before me, perhaps to make sure that he wasn’t followed, that we weren’t seen walking in together.

As I walk toward him, I notice the humid tiles that stick to my shoes, the blue and yellow Formica tables. I imagine the wet sponge that was quickly passed over them as soon as the espresso cups were emptied, the pints of beer consumed. I see old posters of advertisements for Cinzano and Byrrh stuck to the walls, a France from the 1950s. A guy with a stern face stands behind the counter with a ragged towel on his shoulder, as if he just stepped out of a gangster film with Lino Ventura. I feel like an intruder.

Thomas sits at the back of the room trying not to be seen. He’s smoking, or rather he nervously pulls on a cigarette (we still smoked in cafés back then). A draft beer sits in front of him (alcohol was also served to minors). As I approach, I see his nervousness, see that it’s actually just shyness. I wonder if he feels shame. I want to believe that it’s only embarrassment, a question of modesty. I remember, also, that he’s reserved in a way that sets him apart. I could be put off, but instead it moves me. Nothing touches me more than cracks in the armor and the person who reveals them.

When I sit across from him, without saying a word, he doesn’t lift his head at first, keeping his eyes on the ashtray. He taps on his cigarette to make the ashes fall, but he hasn’t smoked it enough. It’s a gesture intended to convey composure, but it only makes him appear more vulnerable. He doesn’t touch his beer. Me, I stay silent thinking it’s up to him to speak first, since he was the one to initiate this strange meeting. I guess that my silence accentuates his discomfort, but what can I do?

I’m trembling. I can feel it in my bones, like when the cold seizes you unexpectedly. I tell myself he has to notice the trembling at least.

Finally, he speaks. I expect something ordinary, to break the ice, something to extricate us from the incongruity of the situation and put us back in the world of the banal. He could ask me how I am, or if I like the place, or if I want something to drink. I would understand those questions and eagerly answer them, happy to let the small talk calm me.

But no.

He says that he has never done this before. He doesn’t even know how he dared, how it came to him. He hints at all the questions, all the hesitations, denials, and objections he had to overcome, but adds that he had to do it, that he didn’t have a choice. It had become a necessity. The smoke gets in his eyes. He says that he doesn’t know how to deal with it, but there it is. It’s given to me as a child would throw a toy at the feet of his parents.

He says that he can no longer be alone with this feeling.

That it hurts him too much.

With these words he enters into the very heart of the matter. He could have delayed or changed the subject. He could have simply left. He might have wanted to check that he wasn’t wrong about me, but he has chosen to offer himself openly to me and to explain, in his own way, what has pushed him toward me at the risk of being compromised, mocked, rejected.

I say: Why me?

It’s a way to go straight to the point, to show him the same candor he has shown me. It’s also a way to validate everything else, everything that’s been said, to get rid of it. To say: I understand, everything is fine, it’s fine with me. I feel the same.

However I am still in shock from what he’s told me, because nothing could have prepared me for it. It contradicts everything I thought I knew. It’s an absolute revelation, a new world. It’s also an explosion, a bullet fired next to an eardrum.

But in that split second I somehow instinctively know that I must rise to the occasion, that he would not bear to see me stammering or in a daze, otherwise everything will crumble to the ground.

I figure that a new question might save us from such a disaster.

The question that imposed itself: Why me?

The image doesn’t fit: my thick glasses, my stretched-out blue Nordic sweater, the student head slaps, the too-good grades, the feminine gestures. Why me?

He says: Because you are not like all the others, because I don’t see anyone but you and you don’t even realize it.

He adds this phrase, which for me is unforgettable: Because you will leave and we will stay.

Even now I remain fascinated by this sentence. Understand, it isn’t the premonition that fascinates me, nor even the fact that it has been realized. It’s also not the maturity or poignancy implied. It’s not the arrangement of the words, even if I’m aware that I probably wouldn’t have been able to come up with those exact ones myself. It’s the violence that the words carry within them, their admission of inferiority and, at the same time, of love.

He tells me something I did not know: that I will leave.

That my existence will be played out elsewhere, very far from Barbezieux, with its leaden skies and stifling horizon. That I will escape as one does a prison. That I will succeed.

That I will seek out our capital city, that I will make my home there, and find my place.

That I will travel the planet, because I was not made for the sedentary life.

He imagines an ascension, some kind of epiphany. He believes me to have a brilliant destiny, convinced that within our little community nearly forgotten by the gods, there are only a few chosen and that I’m among them.

He thinks that soon I will have nothing to do with this world of my childhood, that it will be like a block of ice detached from a continent.

If he had expressed any of this I would have burst out laughing.

* * *

As I’ve said: at that moment in time, I don’t have much ambition. I know I can accomplish long and prestigious courses of study, I’m very disciplined, deferential even, but I have no idea where it will lead me. I imagine that I will have to climb the mountain pass, since I have the qualities of a climber, but the peaks remain imprecise and uncertain; in the end my future is in a fog and I don’t care about it.

I have no idea that one day I will write books. It’s an inconceivable hypothesis. If by some extraordinary chance the idea happened to cross my mind, I would have chased it away. The son of a school principal, an imposter?

Never. Writing books is not a suitable occupation, and above all, it’s not a job, because it doesn’t earn money. It doesn’t offer security or status. It’s also not in the real world. Writing is on the outside. Real life you have to touch, you have to grab it. No, never, my son. Don’t even think about it, I hear my father’s voice saying.

* * *

And as I said: I had no desire to escape. Later, this desire will invade and overwhelm me. It will begin, in the classic way, with an urge to travel to new places, destinations selected from maps and picture postcards. I will take trains, boats, planes, I will embrace Europe, discover London, a youth hostel next to Paddington Station, a Bronski Beat concert, thrift stores, the speakers of Hyde Park, beer gardens, darts, tawdry nights, Rome, walks among the ruins, finding shelter under the umbrella pines, tossing coins into fountains, watching boys with slicked-back hair whistle at passing girls. Barcelona, drunken wanderings along La Rambla and accidental meetings late on the waterfront. Lisbo

n and the sadness that’s inevitable before such faded splendor. Amsterdam with her mesmerizing volutes and red neon. All the things you do when you’re twenty years old. The desire for constant movement will come after, the impossibility of staying in one place, the hatred of the roots that hold you there, Doesn’t matter where you go, just change the scenery, says the lyric to a song.

I remember Shanghai, the teeming crowd, the ugliness of the buildings, an artificial city that doesn’t even preserve the majesty of her river. I remember Johannesburg, its splendor and its poverty. I remember Buenos Aires, people dancing under a volcano, girls with endless legs and older women waiting for the return of their loved ones, the disappeared, a return that will never happen. Later still, the need for exile will put millions of miles and jet lag between France and me, and I will seriously consider moving to Los Angeles for good, never to return. But at seventeen years old, there is none of that.

Thomas Andrieu says that no one can know, everything must stay hidden. That it is the condition: take it or leave it. He puts out his cigarette in the ashtray and finally raises his head. I stare into his eyes, which look somber and determined. I tell him that it’s okay, but his requirement, and the burning in his eyes, scare me.

* * *

A million questions flash through my mind: How did it begin for him? How and at what age did it reveal itself? How is it that no one can see it on him? Yes, how can it be so undetectable? And then: Is it about suffering? Only suffering? And again: Will I be the first? Or were there others before me? Others who were also secret? And: What does he imagine exactly? I don’t ask any of these questions, of course. I follow his lead, accepting the rules of the game.

He says: I know a place.

* * *

The suddenness of the proposition disconcerts me. We were perfect strangers one hour ago, or at least I thought we were, since I had never noticed his desire for me. I didn’t see the looks he had stealthily cast in my direction. I didn’t know that he had asked around about me. So, yes, we were perfect strangers, and then just like that, he asks me point-blank to come with him to who knows where, to do who knows what.

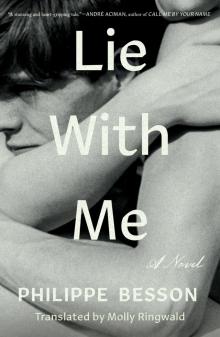

Lie With Me

Lie With Me